It so happens that during a stay with a friend in November I took in a number of Godzilla movies. He has a beautiful Criterion book-set of the Showa-era films, from which we chose 1963’s King Kong vs Godzilla and 1974’s Godzilla vs Mechagodzilla. We also watched the 2021 Godzilla vs Kong US remake – besides various other creature features.

I enjoyed the Godzilla movies. They have their own miniature model aesthetic, a kind of pleasing Harryhausen-like charm that goes a long way. Godzilla vs Kong was the most unspeakable nonsense.

I had no idea of Godzilla Minus One‘s existence until after that trip. I only went to see it to round off Godzilla month. It’s the best thing I’ve seen this year.

There are one or two things about Minus One that are familiar. Having a coward as a protagonist is always going to work for me (Tom Cruise pulls off an excellent yellow belly in Edge of Tomorrow). Opening a story in defeat-era WW2 Japan has also been done in fantasy movies, for instance in that Wolverine samurai movie. Although there it was little more than a striking set piece, rather than integral to the story.

But most of all, watching Minus One, you are struck by how utterly different it feels to other event cinema. The film has so much feeling running through it, such overflowing love, guilt, fear, self-loathing, hope and despair, it achieves something that neither the Showa era nor Hollywood shlock comes close to replicating. In the process, it exposes how emotionally bankrupt Hollywood spectacle movies have become.

Minus One makes it look easy to deliver both heat-ray-breathing, city-smashing, people munching giant terror lizard thrills – and thoughtful exploration of big ideas and interesting characters. It will be fascinating to see if Hollywood tries to respond to this movie. It ought to.

Defeat

Godzilla Minus One is interested in exploring the world of defeat, and the trauma of those who survive it. The film opens with Koichi Shikishima, Kamikaze pilot, electing not to blow his brains out for the emperor. Instead he lands at an airfield, pretending to have engine trouble – a location that is promptly attacked by Godzilla. Everybody dies but him and one other.

He returns to Tokyo a shell of a man, a creature bent under the weight of guilt. He finds his parents have died in air raids and his city is a charred ruin.

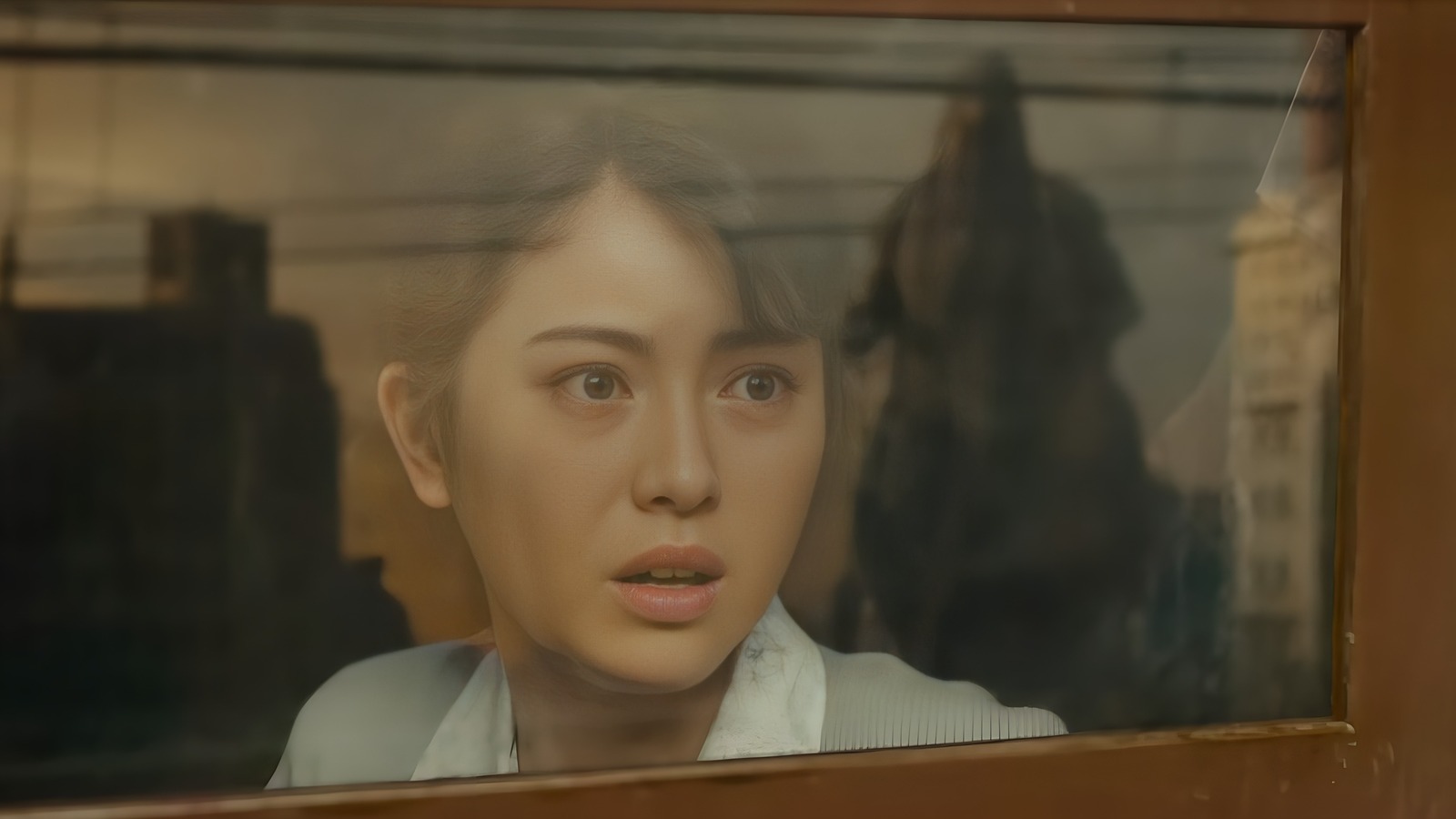

In the ashes he meets Noriko Oishi, a homeless woman caring for a baby, Akiko. Reluctantly he takes responsibility for them and the three form a family, along with a traumatised neighbour who lost her children in the air raids.

For long periods the monster is peripheral as the movie concentrates on developing these characters. Through Shikishima’s story, it deals with themes of trauma and guilt, fear of fatherhood, and hope rising from a wasteland.

Because the movie is taking its time over these people, being careful to make them real, this completely pays off – when Godzilla returns, we care about what happens to them.

Anti-war

A truly great anti-war film has the capacity to be far more moving than the best war movie. Godzilla Minus One has a powerful message built on stamping on Samurai mystique: that seeking honrouable death for the emperor is bullshit; that war traumatizes long after the shooting stops; and that fighting is only a legitimate impluse when it is to try and survive, for the the future and one’s family.

The team that take on Godzilla do so on their own initiative, without the help of the Japanese government or the curiously absent Americans, who throw a shadow over all of this, having mutated Godzilla with their nuclear weapons, slaughtered civilians with air raids, and now as occupiers, abandoned responsibility for Japan’s defence.

This isn’t as pure an anti-war message as it could be. Godzilla MInus One flirts with admiration for Japanese end of war military technology, which nearly muddied the message for me: the use of the Kyushu J7W Shinden is reminiscent of aviation nerds’ slightly suspect “what if” passion for Nazi jet technology. But this is a minor quibble. The main message is adhered to. Shikishima refuses to die in the aircraft to appease his ghosts, choosing life instead.

Skills and budgets

It’s not only the message and the characters that work. This is another case of a movie where a budget forces more selective and interesting creative choices from its director.

The sequence in which Shikishima and comrades fight Godzilla from their one little boat, tossing recovered mines at a pursuing lizard, is a hell of a lot more exciting than the kind of braindead titan clashes that characterize Hollywood creature feature output like Godzilla vs Kong.

Scale is better deployed here, moments better chosen: like the scene where we see a burning piece of destroyer hurtle across the docks, heralding Godzilla’s imminent arrival. His attack on the city feels genuinely devastating.

The human factor

Still, most of all, Godzilla Minus One‘s major accomplishment remains its character development.

Sitting there in the cinema, it felt genuinely strange to be treated as if I might both enjoy a movie that offers both monsters and intimate human drama. It certainly felt incredibly odd to weep at a moment in a movie about a giant lizard attack on Tokyo. But I did, twice.

Yes, I am a tearful sap. But the fact that the movie refuses to abandon character work for pure spectacle is its greatest triumph. In the process, it casts the most damning shadow on Hollywood’s comic book movie age, where characters are little more than mr and mrs perfects, interchanging quips during impatient intervals in the thumping great action.

The movie has thrown down a gauntlet to Hollywood it seems to me: can you do something even half this good with your vast budgets?

The trailer for Godzilla x Kong played before Minus One. On that evidence, Hollywood is a long, long way away.