Legions of microscopic robots fascinate scifi writers, from Star Trek’s Borg nanoprobes to the power-outage swarm of Revolution. In each case nanotech is a tyrant, reducing people to little more than slavery – to a soulless, technological ‘hive mind’ in the first; to a brutal, pre-electric dictatorship in the second.

Our primitive understanding of microbiology hardwires us, it seems, to view artificial microscopic agents with suspicion – as contaminating fifth columnists, or agents of chaos.

Engineers have brighter ambitions for nanotechnology. Barriers to developing effective nanorobots are enormous, but baby steps are being taken. The Engineer reported this month on a miniature robot formed of a layer of biodegradable ‘Biolefin’ that, once swallowed, expands in the stomach, taking on a rectangular shape with accordion folds.

It’s thought embedded magnets could allow it to be controlled externally, employed to remove foreign objects from the stomach, patch wounds, or deliver medication to a specific point in the digestive system.

This is only the beginning of engineers’ hopes for nanotech healthcare. Researchers plan magnetically charged nanobots controlled via MRI technology, used to dredge clogged arteries of fatty deposits, and diagnostic nanobots that float about our bodies, detecting cancer nodes and delivering targeted treatment – ending carpet bombing solutions like chemotherapy.

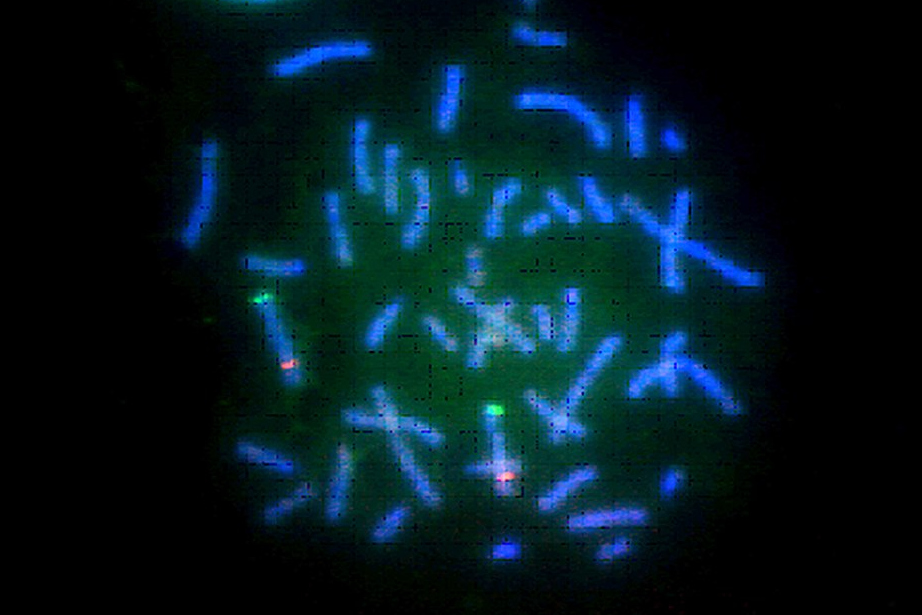

Even the materials of which such nanobots might be made is mind-boggling; atom thick graphene strips folded in complex origami patterns; DNA strand shoestrings which untie to release antibody payloads.

Nanotech ships

To the scifi mind these plans feed our conception of the human body as a kind of alien landscape, a frontier that we are exploring and learning to tame. In stories like Inner Space and Futurama’s ‘Parasites Lost’ episode, nanobots are really shrunken spacecraft, vessels for miniaturised people. They are helmed by atom-sized pilots on fantastic voyages, where heart, lungs and orifices are vast geological features. Often our plucky explorers learn to manipulate their hosts – playing with their senses, appearance, and intelligence.

As writers we might be tempted to explore this notion of man exploring man a little further. In the age of dying privacy it’s easy to imagine nanobots used as the agents of the surveillance state – what better way to follow your target than to have him carry his own spies inside him?

In fact, what better way to assassinate him? We could follow the adventures of some nano spook whose adapted bots destroy enemies of the state from within, stimulating cancer, furring up arteries and provoking strokes. They are so successful that enemies are vanquished entirely, and our hero is turfed out of a job. Good for nothing but snooping, he turns his toys to the freelance service of gossip media, discovering an enormous market for nanobot photography of celebrity breast implants, tumours and bloodclots shot from within.

Nanotech minds

Even the most utopian visions of nanotech can be given a gloomier twist. Futurist Ray Kurzweil posits a nanobot future of Godlike intelligence and immortality. Nanotech will allow our minds direct access to the cloud, he believes, feeding knowledge directly into our brains. The same tech, he states, will back up our memories and thoughts, allowing us to live on as electronic reproductions.

But really, how God like would someone plugged into the world’s cloud of free ‘information’ be? Could nanotech overcome our own confirmation bias?

Research shows that we tend to find ourselves in ‘echo chambers’ online, which reinforce our existing worldviews, true or not. A story could trace the fortunes of a tribe of technologically advanced but terminally misinformed conspiracy buffs – certain in their ‘knowledge’ that the moon landings were faked. By being permanently plugged into the feedback loop of misinformation, they become radicalised, burning NASA installations and butchering rocket scientists in frenzied revenge attacks, setting back space exploration by fifty years, but confident in their utterly clueless cause.

Nanotech immortality

As for immortality, isn’t death part of what drives us to seize life? Besides, who would really want their loved ones around forever? A story could follow one poor wretch condemned to live with the bot memory of her parents for all eternity, a kind of endless Christmas dinner of criticism, embarrassing anecdotes and arguments about politics.

Money distorts most of our visions of the future, and with nanotech it’s no different. SciFi has plenty of Gattica like worlds, where the wealthy are near immortal bot-maintained cyborgs, sealed in a perfect tyranny. Perhaps our best hope lies in the nanobots taking the initiative themselves; ensuring an equitable spread of appropriate enhancements to mankind, and filtering the information we access.

This chimes with Kurzweil’s most optimistic vision, of using bots to expand the neocortex, creating more profound means of expression – music and art that we could not imagine now.

Or perhaps, becoming equally exquisite examples of humanity, we’ll become so unbearably self-satisfied we’ll have no need of such distractions. Whatever the case, a world taking a bot-inspired evolutionary leap will surely have entirely new stories to tell – but without the nanotech, who can guess what they might be?