I never watched this when it came out, and now that I view it, I trust my initial instinct.

It’s not a bad film. It’s well made – of course it is, Marty is putting it together. Scorcese doesn’t bother too much about rigid adherence to timeline and tune. There’s a bit of footage I’d not seen before, though not much. Dhani Harrison reads out some of George’s letters to his mum, which is a nice touch.

But there is a word hanging over the production that is not a good word, and that is ‘anthology’. There is the same powerful sense here of a very strictly authorized biography, of the truth regularly being approached and then backed away from. The movie skirts around difficulties, slips over great chunks of time, in favour of uplifting official lore.

That means that if you watched the anthology as a teenager and then watch Living in the Material World there is not a huge amount to learn, save some nice bits and pieces about his childhood:

McCartney reminisces that George’s school pal used to call his slicked up quiff a ‘fucking turban’ and that Dickens had taught at their school; George’s brother remembers John Lennon pouring a pint over an elderly woman piano player’s head at his wedding. It’s also nice to think of Derek Taylor’s kids growing up taking trips to mad Uncle George’s Country House of Wonders.

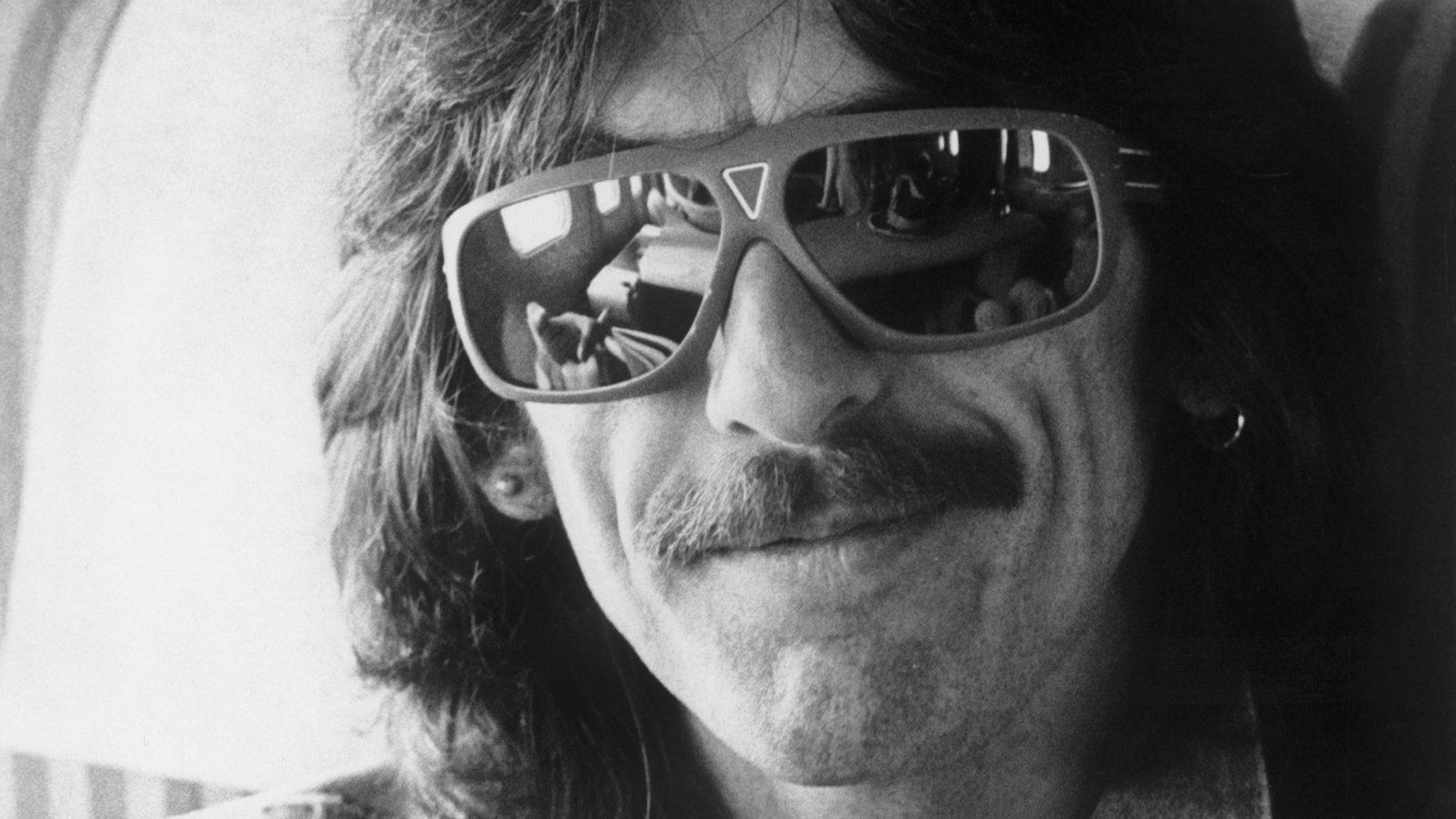

An elusive bugger

But George’s personality remains elusive, and the sense is that some of the speakers offered plain speaking which is not shared here: that there’s been agreement merely to state that he had another side, but focus on the spirituality.

Fine, sure, I can understand that. But it does mean we’re not really learning much about him as a real person. Even Imagine showed one instance of Lennon losing his shit. Here there is no footage that shows an even vaguely negative aspect of George.

Gilliam, Ringo, and McCartney all imply that there was a considerably more flawed side to their friend beyond the undoubtedly kind, funny and spiritual person he could be – put the pieces together and there is the shadow of someone who could be angry, exhaustingly difficult, and mean with his ‘bringing the truth’ shit.

Klaus V says George got into drugs in the 70s: this is then never mentioned again. It is vaguely hinted at that the Dark Horse tour was a disaster, but not investigated. Scorcese can’t wait to jump clear of All Things Must Pass into the Wilbury period, even though that episode would be all the more uplifting if he took the time to first walk us through the relative musical decline of the mid 70s and early 80s.

That, in the end, is the sadness watching this. McCartney 3,2,1 showed that by focussing on the music, you can draw a Beatle out in interesting new ways, get beyond the tired old stories and learn something genuinely new, and perhaps more interesting than friends and relations memories. There is one tantalising moment of that here, when George Martin remembers turning down George’s first submission for Sgt Pepper – likely Only a Northern Song – which he plainly states was ‘boring’.

A tricky bugger

That song in itself provides no little insight into the tricky bugger George could be, both to know and to work with. Only a Northern Song was an obvious complaint, a dirge, and a kind of ‘fuck you’ to John and Paul and the Beatles operation. Yet he seems to have insisted it be recorded, which must have grated, just as hammering away 100 takes of ‘Not Guilty‘, another obvious moan about his position in the band did.

A Rubin-like figure, approaching George about the recording process of these songs, might have drawn him out on his Beatles position. Similarly, walking him through his excellent guitar on How do You Sleep? might have opened a window on those weird, post break-up days when he seems to have still enjoyed playing with John.

This very traditional documentary examines his musical legacy leaning heavily on the sitar, Ravi Shankar and Indian music, which while hugely important really defined quite a small part of his actual output.

Discussion of some select tracks from his 70s work would give a more complete picture of him as a songwriter and artist, giving due credit to some solo albums that some of us think deserve a second look.

Overall, George’s music is mainly background here for Scorcese’s attempt to get to the man through the anecdotes of friends, family, and collaborators – and his own (slightly droning) memories of his spiritual journey. In this, it falls a little flat, and George remains elusive even after three hours.

It is sad that we’ll never get the in-depth interrogation of George and his music, the way McCartney had with Rubin. However, it must be said, I’m not sure George would want we maniacs to have too much insight anyway. I can imagine him telling Rubin nothing new at all – just to be a difficult bugger.